Matplotlib visualization tips that make plots speak for

themselves

A picture is worth a thousand words. Good visualizations speak for

themselves saving the expensive stakeholders' time while presenting a

data project. Unfortunately, raw data exploration plots are not suitable

for sharing with audience no matter how good the visualization library

is. The visualizations require fine tuning to make them easy to navigate

for an untrained eye. Otherwise, a large chunk of the meeting is wasted

on explaining what is on the plot rather than talking about the

implications. Though tempting, such tradeoff can push a decision on a

critical project by weeks or months.

In this blog, I will share the pieces of code that make

visualizations easier to read and approaches for saving time while

putting the corresponding code together. The material is intended for

the Data Scientists who spend significant time exploring the data and

using the results to help stakeholders make business decisions.

The last mile problem

Python community owns a number of powerful visualization libraries.

Seaborn,

Plotly,

Altair,

Pygal, and

Plotnine are among the

many others. The libraries compete in how much insights they can cram in

one graph with a single plot command. This helps

tremendously in data exploration and discussing intermediate results

with fellow data scientists. However, the business stakeholders get

confused with the complexity of such elaborate visualizations especially

if presented in a raw form. They did not read the dataset documentation

to guess that cty on x axis is the fuel consumption in

the city, may not be aware of the average for the industry to compare it

with, or did not have a training about where to look at in a box plot.

It is on us to make the graphs easy to read. I data professional is

responsible for focusing stakeholders' attention on the things they want

to know. This last mile from a flashy picture to an informative graph

requires a significant effort.

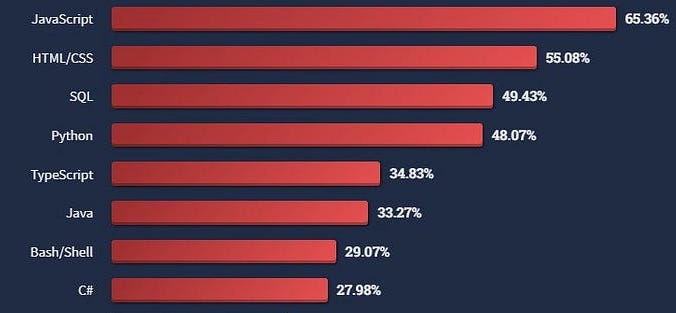

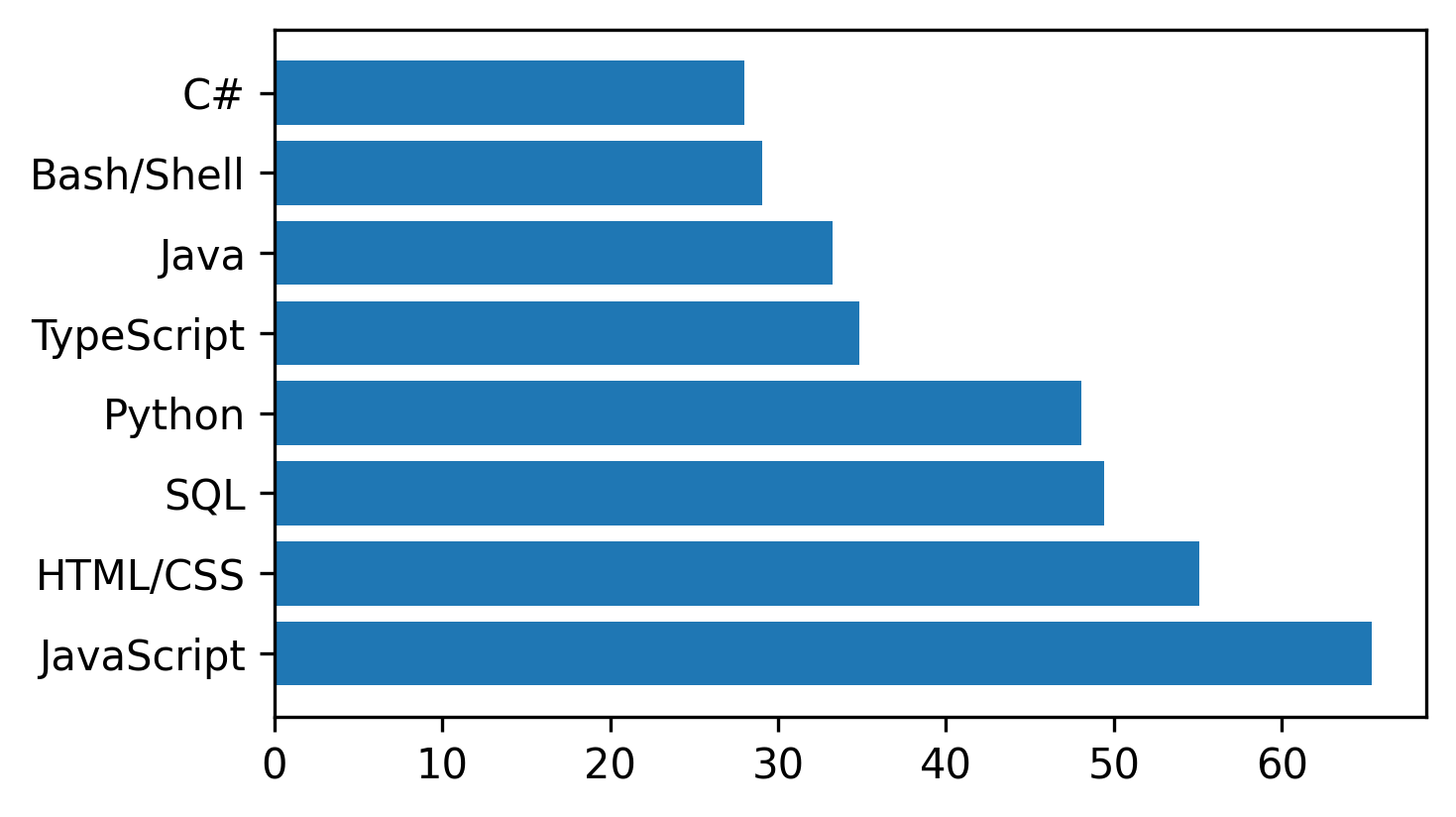

Let's say, I found a function from a new visualization library that

fits perfectly to my data and renders the following plot that I found in

this

article:

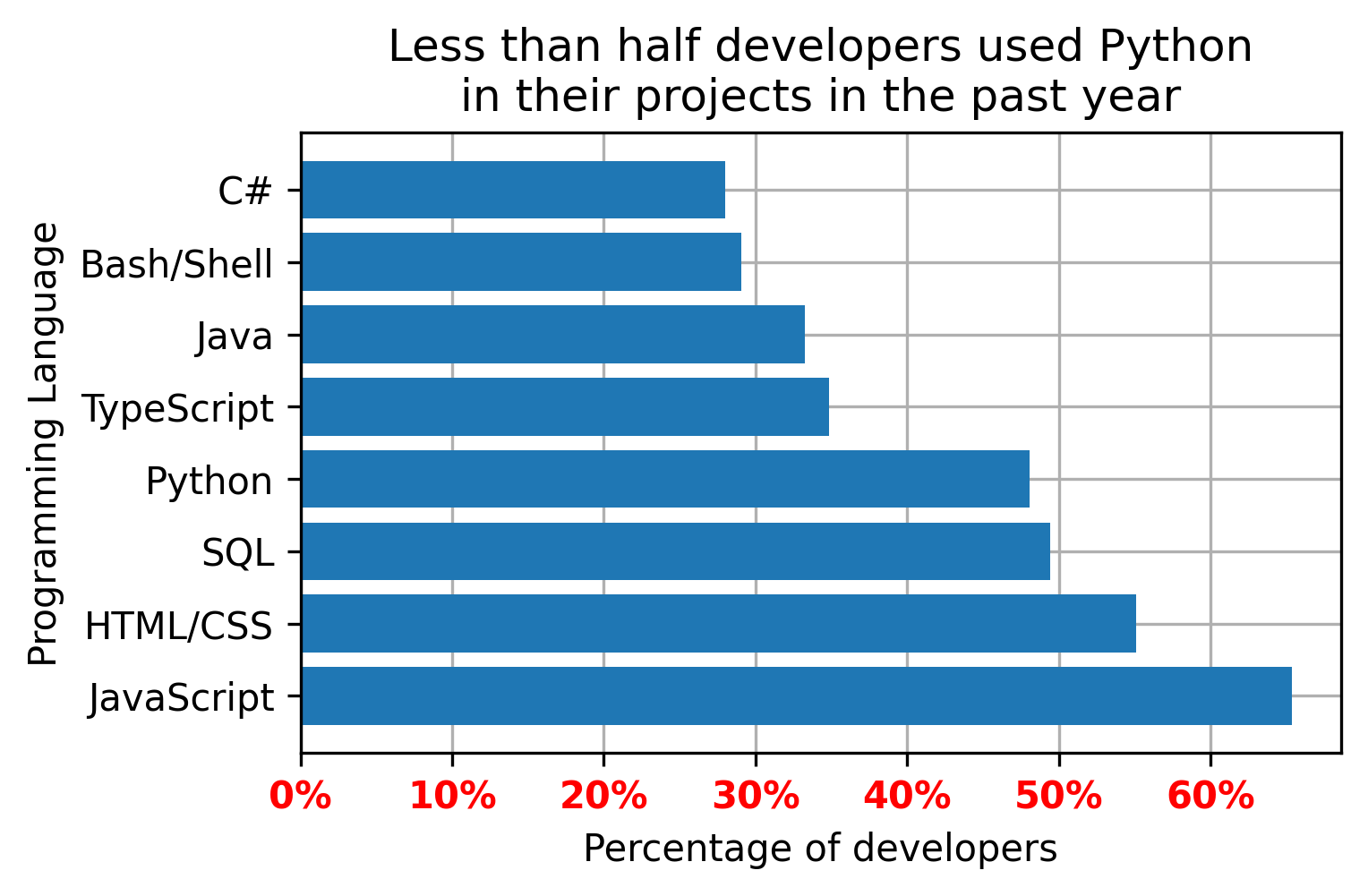

Looks slick, but I will have to spend time explaining what was

measured for each of the programming languages. Even after that, it is

unclear what message I want to get across and where to look for

justification. Each mental step that a stakeholder has to take while

reading the plot increases the chances of misinterpretation and the

overall confusion. Such simple steps as adding an x label or writing a

title do the job but get often omitted. Memorizing the corresponding

commands for each new library or googling the documentation every time

is not impossible but tedious. Instead, I want concentrate on the tricks

that cover the last mile using the standard matplotlib

library. There are two reasons for that:

- Inheritance.

Some visualization libraries like Seaborn use

matplotlib as

a backbone. This means that the generated image can then be finished off

in the same way as if it was generated with matplotlib

itself. - Sufficiency.

matplotlib provides

all the essential visualization functionality. The result might not be

as flashy or interactive but has all the means for bringing the point

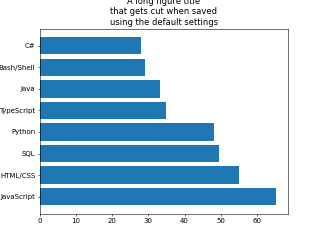

across efficiently. For example, the above visualization can be

delivered with the standard library in the way shown below.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

programming_languages = ('JavaScript',

'HTML/CSS',

'SQL',

'Python',

'TypeScript',

'Java',

'Bash/Shell',

'C#')

past_year_use = (65.36, 55.08, 49.43, 48.07, 34.83, 33.27, 29.07, 27.98)

plt.barh(programming_languages, past_year_use)

plt.show()

The bare bones plot with matplotlib contains exactly the

same information but looks even less intuitive then the original image.

The following section will cover the steps on how to make this plot easy

to read. The section after that will show ways of saving time on the

tuning process.

Making plots easier to read

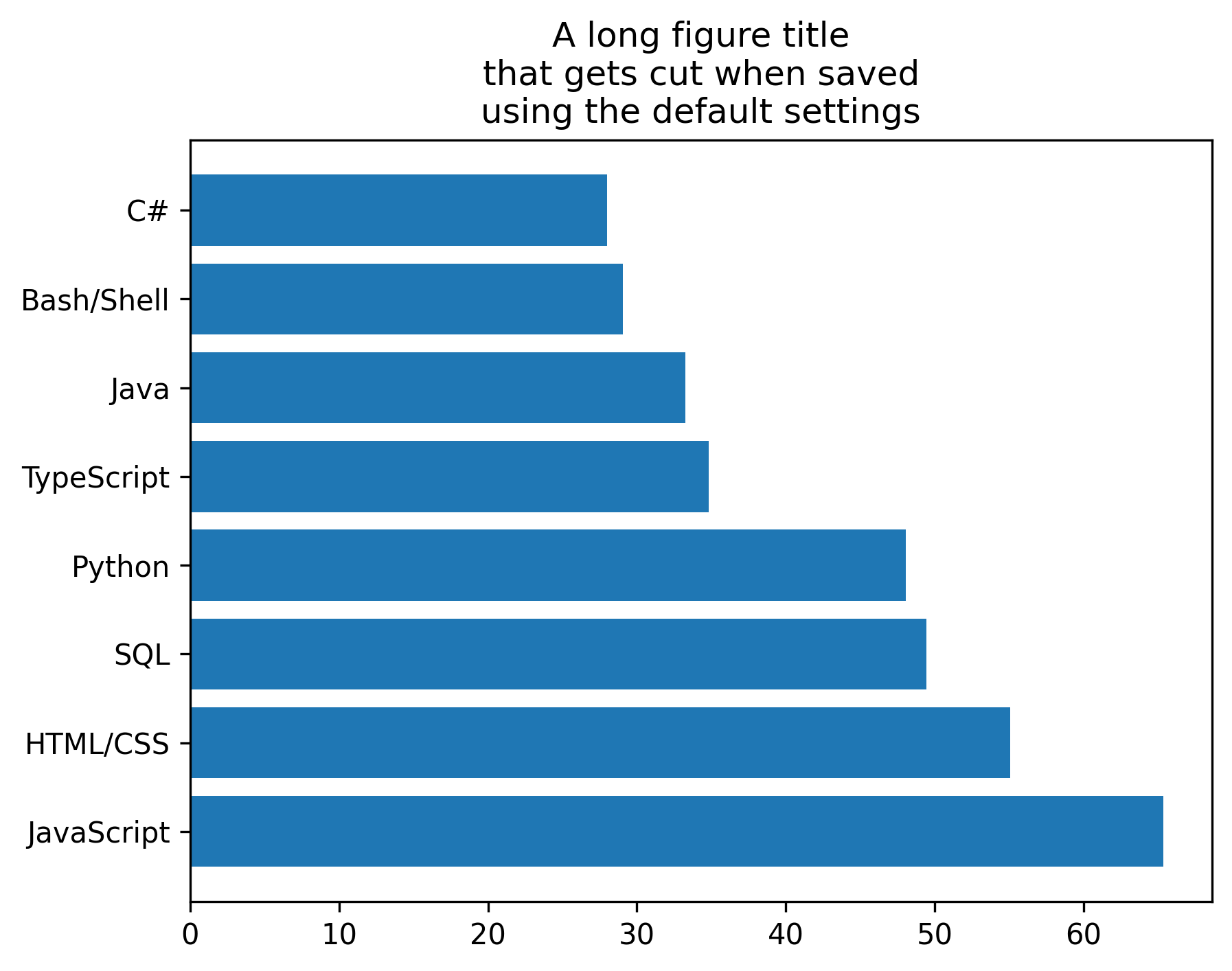

Image saving options

The resulting plot will only appear on slides or in documentation if

it was saved in a file. However, the default saving options need

adjustments more often than not. Default framing settings can cut parts

of the header out of image while the default resolution settings can

result in a pixelated outcome.

It is our responsibility to make sure the final result looks good on

the screen where it is presented. The bbox_inches='tight'

parameter makes every piece of the plot fit and cuts the excessive white

space. The dpi parameter controls the resolution.

Increasing the dpi value results in less blurry images in

expense of the increasing file size.

plt.savefig('pics/demo_bar_plot_save.png', bbox_inches='tight', dpi=300)

# plot preparation

fig = plt.figure(figsize = (5,3)) # set the figure size (Width, Height)

ax = plt.gca() # get the axis from the plot

# plotting

handle_bars = plt.barh(programming_languages, past_year_use) # the plot

plt.savefig('pics/demo_bar_plot_fs.png', bbox_inches='tight', dpi=300)

plt.show()

Title and axis labels

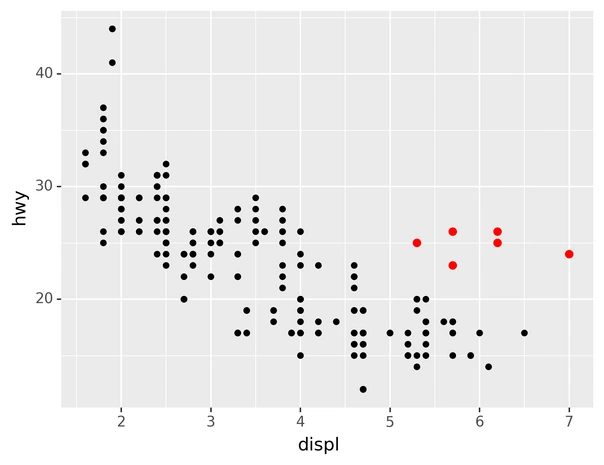

The plot should inform the viewer about its content. Most

visualization tutorials describe only the part of putting a graph

together while leaving the context dependent code up to the readers. The

following example from

this tutorial does

its job demonstrating the library capability. However, it should never

appear on presentation slides in its raw form:

Even though

the plot hints to something by coloring some of the dots red, it takes a

mental effort to figure out what the axis are and why the red dots are

important. Title and labels are a straightforward way of delivering this

information. Assumptions about these details being obvious lead to

confusion, misinterpretations, unnecessary questions, and lengthy

explanations. A simple remedy would be to always label the axis and tell

the readers the main takeaway of the plot in the title. Say, I want

bring across the point that, unlike my expectations, Python is not as

wide spread in developers' projects as some other programming languages.

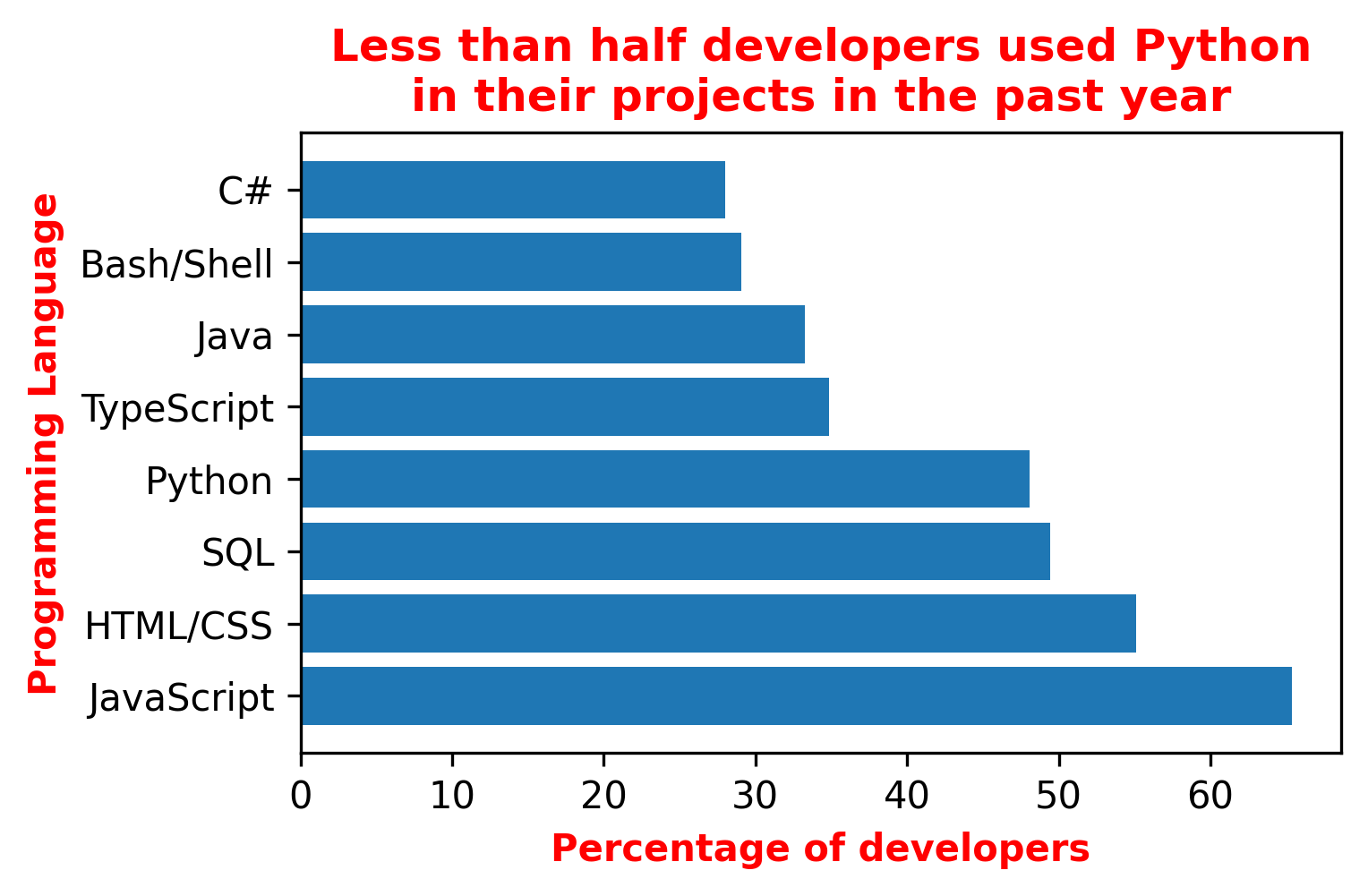

Then I would set the title and the axis as follows:

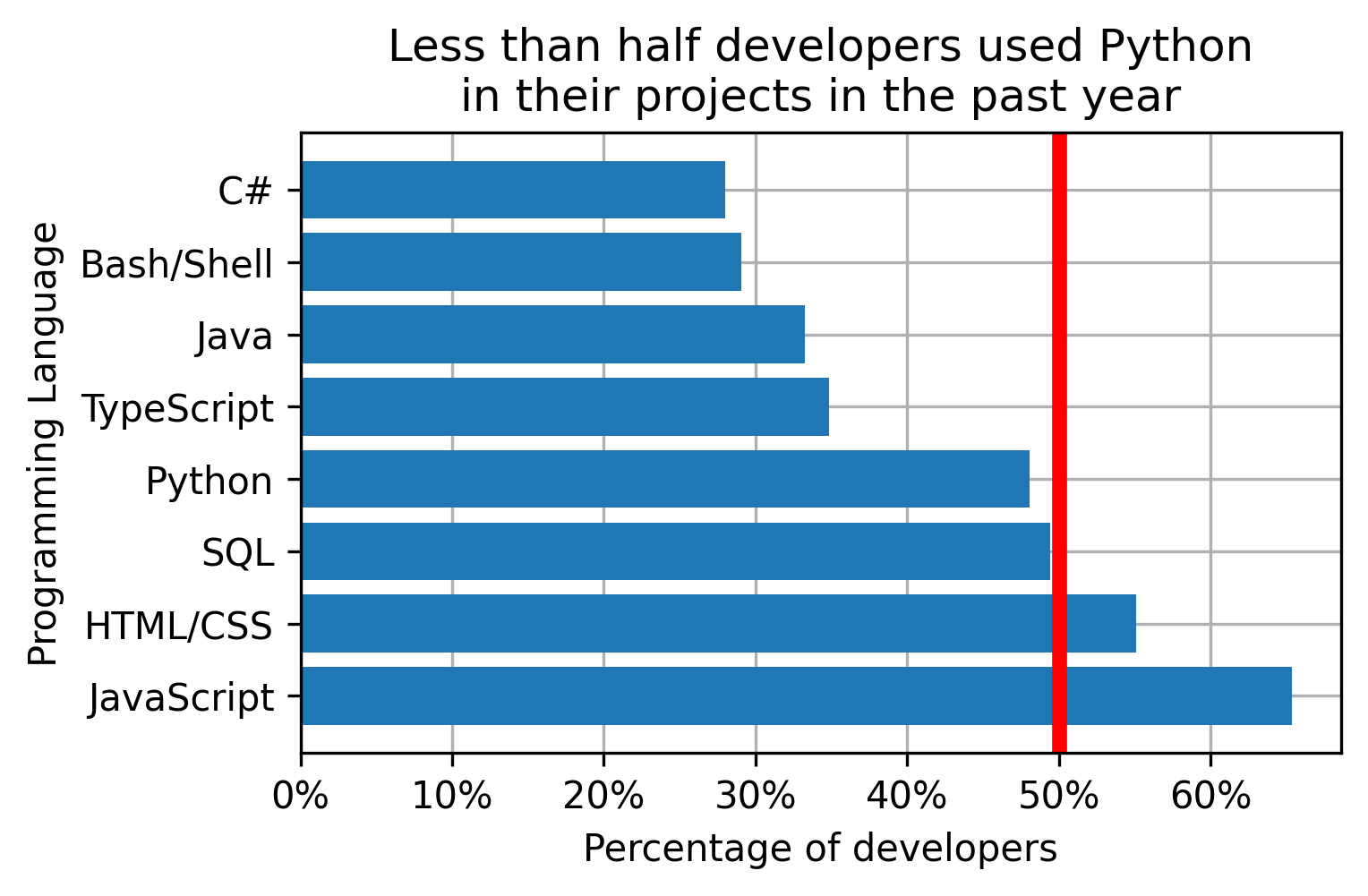

plt.title('Less than half developers used Python\n'

'in their projects in the past year')

plt.xlabel('Percentage of developers')

plt.ylabel('Programming Language')

This will still force my reader to make an effort finding the Python

bar and comparing its length to the others but the focus is already

there.

# plot preparation

fig = plt.figure(figsize = (5,3)) # set the figure size (Width, Height)

ax = plt.gca() # get the axis from the plot

# plotting

handle_bars = plt.barh(programming_languages, past_year_use) # the plot

# fine tuning

highlighting = {'color':'red', 'fontweight':'bold'}

plt.title('Less than half developers used Python\n'

'in their projects in the past year',

**highlighting)

plt.xlabel('Percentage of developers', **highlighting)

plt.ylabel('Programming Language', **highlighting)

plt.savefig('pics/demo_bar_plot_ttl.png', bbox_inches='tight', dpi=300)

plt.show()

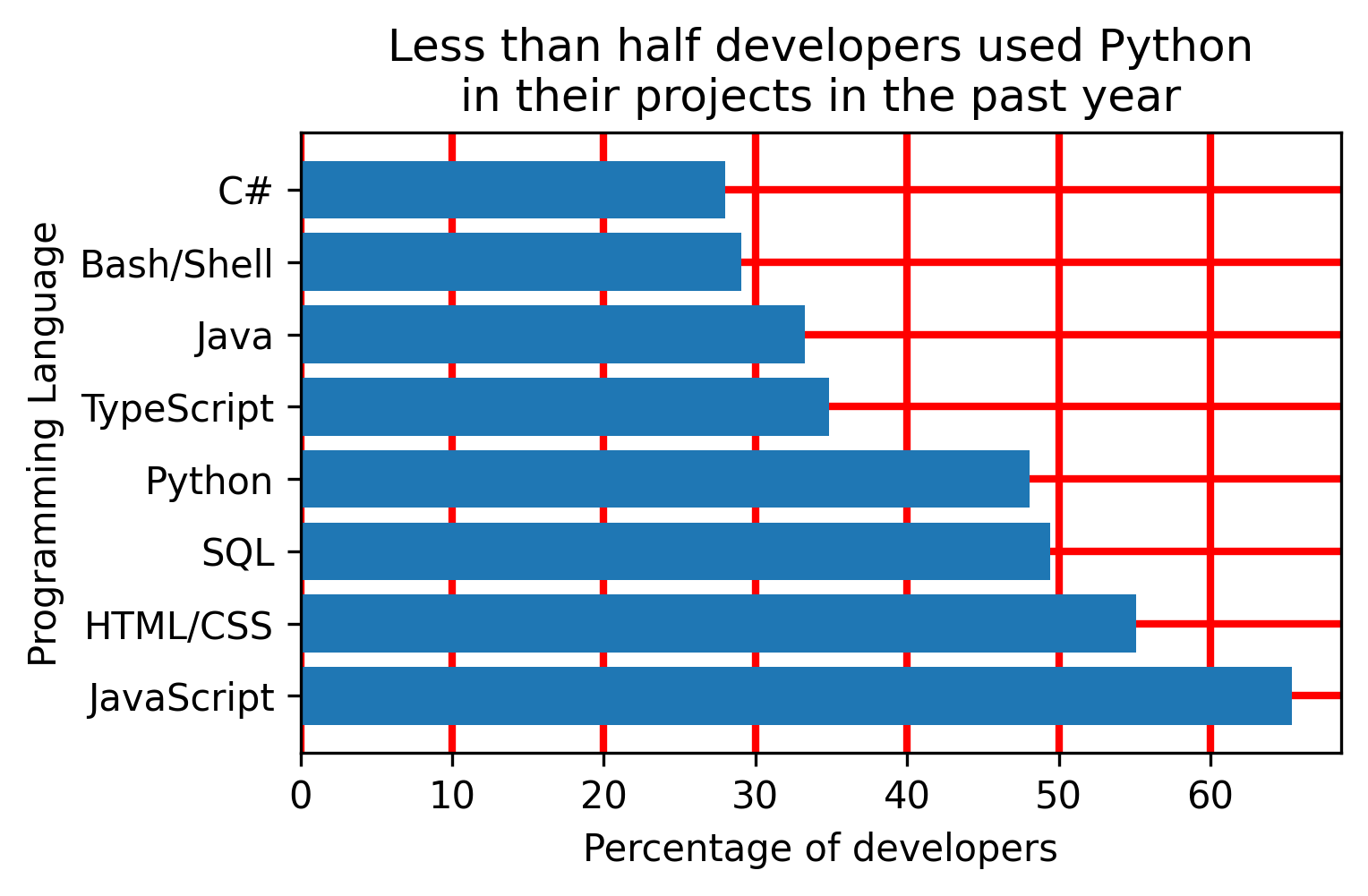

Grid lines

Grid lines help perceive the differences between the values on a

plot. The effect is similar to how the lines on the football field help

referees spot the differences between players' positions when calling

offsides.

The following command sets the grid:

plt.grid(True) # show the grid

However, the grid lines show up on the top of the bars by default.

And that looks ugly. The fix requires extracting the axis object from

the plot first before setting the grid below the bars:

ax = plt.gca() # get the axis from the plot

ax.set_axisbelow(True) # set grid lines to the background

# plot preparation

fig = plt.figure(figsize = (5,3)) # set the figure size (Width, Height)

ax = plt.gca() # get the axis from the plot

# plotting

handle_bars = plt.barh(programming_languages, past_year_use) # the plot

# fine tuning

plt.title('Less than half developers used Python\n'

'in their projects in the past year')

plt.xlabel('Percentage of developers')

plt.ylabel('Programming Language')

plt.grid(color='red', linewidth=2) # show the grid

ax.set_axisbelow(True) # set grid lines to the background

plt.savefig('pics/demo_bar_plot_gl.png', bbox_inches='tight', dpi=300)

plt.show()

# plot preparation

fig = plt.figure(figsize = (5,3)) # set the figure size (Width, Height)

ax = plt.gca() # get the axis from the plot

# plotting

handle_bars = plt.barh(programming_languages, past_year_use) # the plot

# fine tuning

plt.title('Less than half developers used Python\n'

'in their projects in the past year')

plt.xlabel('Percentage of developers')

plt.ylabel('Programming Language')

plt.grid(True) # show the grid

ax.set_axisbelow(True) # set grid lines to the background

ax.set_xticklabels(ax.get_xticks(), color='red', weight='bold')

add_percentage = lambda value, tick_number: f"{value:.0f}%" # function that adds % to tick value

ax.xaxis.set_major_formatter(plt.FuncFormatter(add_percentage)) # apply the tick modifier to x axis

plt.savefig('pics/demo_bar_plot_tl.png', bbox_inches='tight', dpi=300)

plt.show()

Reference points

Points of reference help navigate the audience around the

expectations like the sales goal, an industry standard, the end of

quarter, or something of high importance. Adding a reference point

explicitly saves efforts in making sense of the plot.

I added a vertical line at 50% of programmers who used a programming

language. This makes it easier to get an understanding of the graph and

to make the right conclusions without looking at the numbers (e.g. less

than 50% of the programmers use Python).

plt.axvline(50, color='m', ls='--') # 50% cutoff vertical line (axhline for horizontal)

# plot preparation

fig = plt.figure(figsize = (5,3)) # set the figure size (Width, Height)

ax = plt.gca() # get the axis from the plot

# plotting

handle_bars = plt.barh(programming_languages, past_year_use) # the plot

# fine tuning

plt.title('Less than half developers used Python\n'

'in their projects in the past year')

plt.xlabel('Percentage of developers')

plt.ylabel('Programming Language')

plt.grid(True) # show the grid

ax.set_axisbelow(True) # set grid lines to the background

add_percentage = lambda value, tick_number: f"{value:.0f}%" # function that adds % to tick value

ax.xaxis.set_major_formatter(plt.FuncFormatter(add_percentage)) # apply the tick modifier to x axis

plt.axvline(50, color='r', linewidth=4) # 50% cutoff vertical line (axhline for horizontal)

plt.savefig('pics/demo_bar_plot_rp.png', bbox_inches='tight', dpi=300)

plt.show()

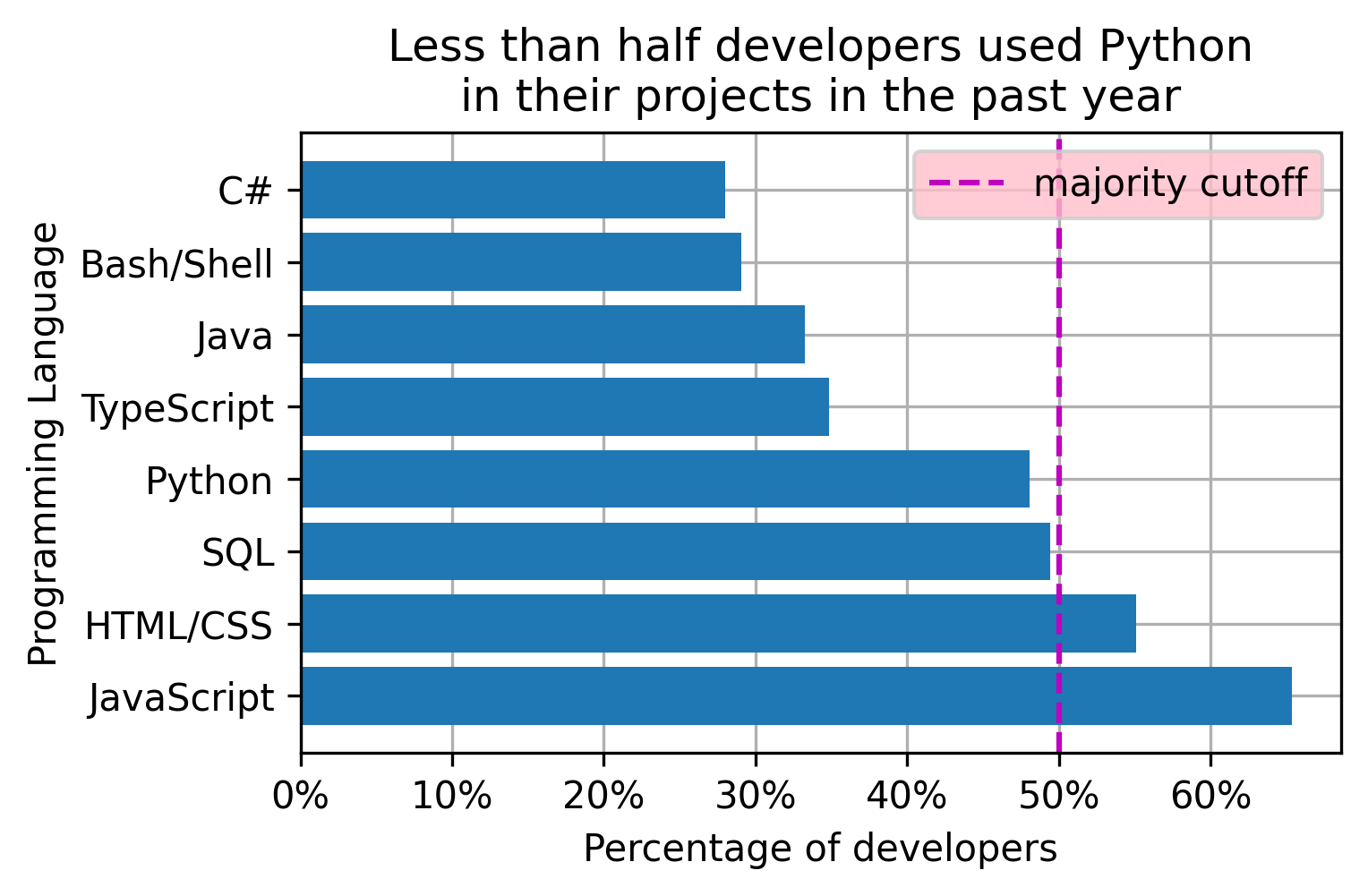

Legend

A legend names different layers of the plot. The default order of the

layers can be mixed up. In such cases individual layers can be

identified through the corresponding handles and added individually with

the corresponding names. In my example, the legend for the bars

themselves will not add value while taking space, but the reference line

should be annotated. The location argument helps positioning the legend

in a way that does not obstruct the areas of high importance.

handle_vline = plt.axvline(50, color='m', ls='--') # 50% cutoff vertical line (axhline for horizontal)

plt.legend([handle_vline], # layers handles

['majority cutoff'], # layers names

loc='upper right') # legend position

# plot preparation

fig = plt.figure(figsize = (5,3)) # set the figure size (Width, Height)

ax = plt.gca() # get the axis from the plot

# plotting

handle_bars = plt.barh(programming_languages, past_year_use) # the plot

# fine tuning

plt.title('Less than half developers used Python\n'

'in their projects in the past year')

plt.xlabel('Percentage of developers')

plt.ylabel('Programming Language')

plt.grid(True) # show the grid

ax.set_axisbelow(True) # set grid lines to the background

add_percentage = lambda value, tick_number: f"{value:.0f}%" # function that adds % to tick value

ax.xaxis.set_major_formatter(plt.FuncFormatter(add_percentage)) # apply the tick modifier to x axis

handle_vline = plt.axvline(50, color='m', ls='--') # 50% cutoff vertical line (axhline for horizontal)

plt.legend([handle_vline], # layers handles

['majority cutoff'], # layers names

loc='upper right', # legend position

facecolor='pink')

plt.savefig('pics/demo_bar_plot_lgnd.png', bbox_inches='tight', dpi=300)

plt.show()

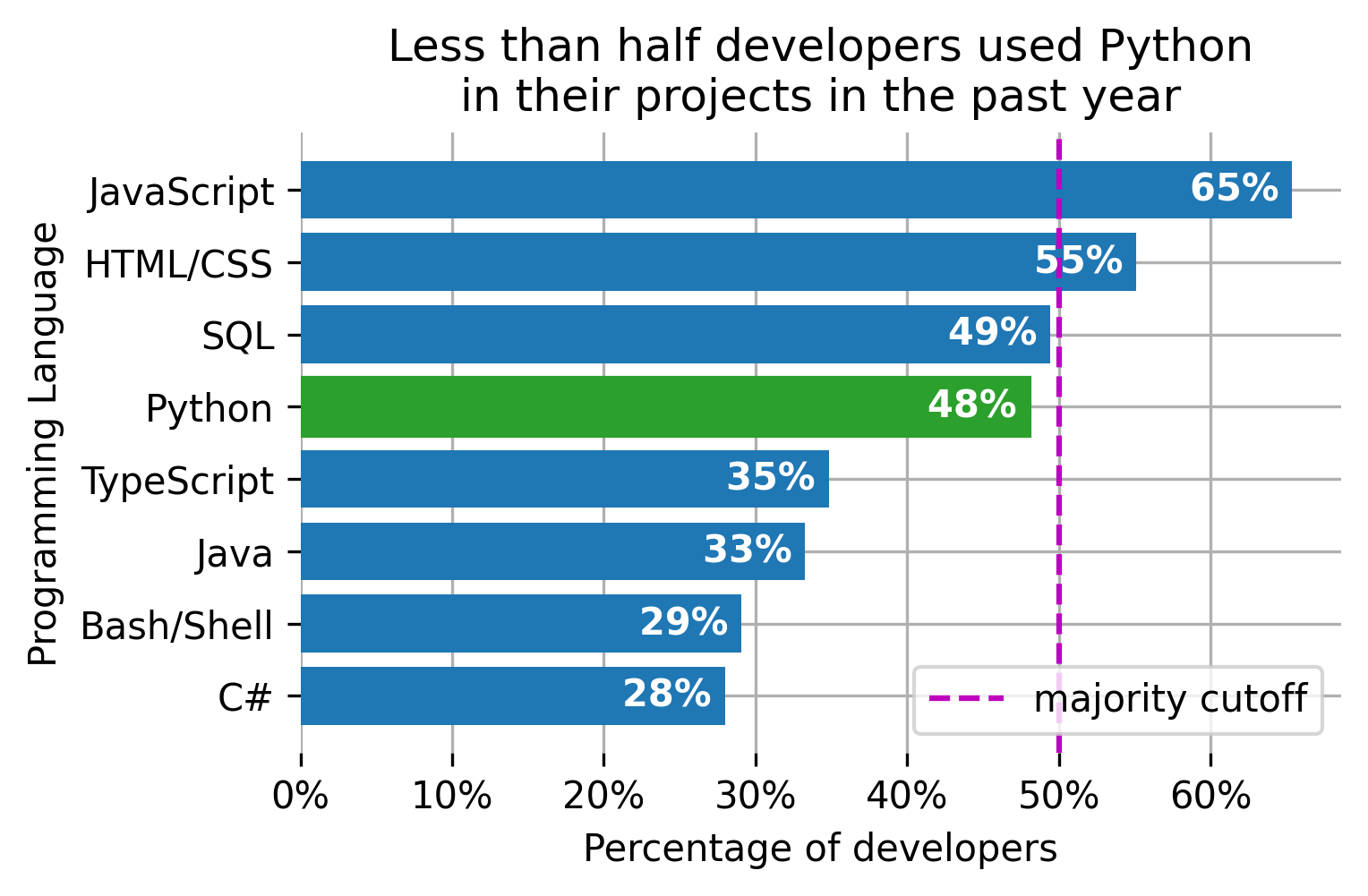

Plot specific manipulations

The above manipulations are applicable to the major plot types

including line plots, bar plots, box plots, etc. Plot specific

manipulations can also help in delivering the message. The horizontal

bar plot from my example can benefit from highlighting the bar of

interest, listing the bars in a descending order, and adding the values

numbers to the bars.

python_ix = programming_languages.index('Python') # find the Python bar position

handle_bars[python_ix].set_color('C2') # set the Python bar to a different color

ax.invert_yaxis() # make bars display from top to bottom vs the default

for pos, val in enumerate(past_year_use): # print values on the bars

ax.text(val, pos, f'{val:.0f}% ',

verticalalignment='center', horizontalalignment='right',

color='white', fontweight='bold')

plt.box(False) # turn off the box

# plot preparation

fig = plt.figure(figsize = (5,3)) # set the figure size (Width, Height)

ax = plt.gca() # get the axis from the plot

# plotting

handle_bars = plt.barh(programming_languages, past_year_use) # the plot

# fine tuning

plt.title('Less than half developers used Python\n'

'in their projects in the past year')

plt.xlabel('Percentage of developers')

plt.ylabel('Programming Language')

plt.grid() # show the grid

ax.set_axisbelow(True) # set grid lines to the background

add_percentage = lambda value, tick_number: f"{value:.0f}%" # function that adds % to tick value

ax.xaxis.set_major_formatter(plt.FuncFormatter(add_percentage)) # apply the tick modifier to x axis

handle_vline = plt.axvline(50, color='m', ls='--') # 50% cutoff vertical line (axhline for horizontal)

plt.legend([handle_vline], # layers handles

['majority cutoff'], # layers names

loc='lower right') # legend position

# plot specific modifications

python_ix = programming_languages.index('Python') # find the Python bar position

handle_bars[python_ix].set_color('C2') # set the Python bar to a different color

ax.invert_yaxis() # make bars display from top to bottom vs the default

# print values on the bars

for pos, val in enumerate(past_year_use):

ax.text(val, pos, f'{val:.0f}% ',

verticalalignment='center', horizontalalignment='right',

color='white', fontweight='bold')

plt.box(False) # turn off the box

plt.savefig('pics/demo_bar_plot.png', bbox_inches='tight', dpi=300)

plt.show()

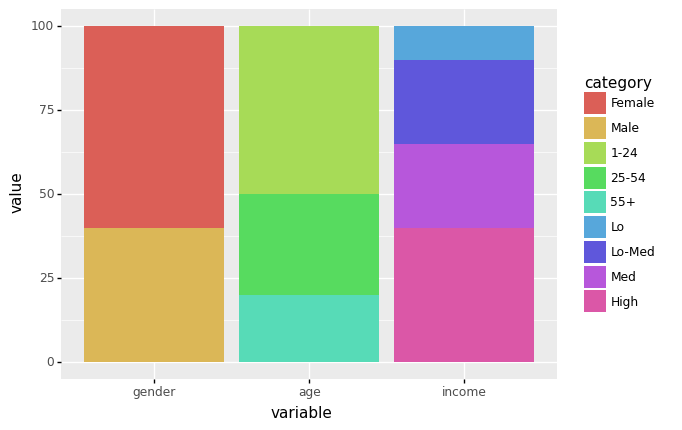

Lather, Rinse, Repeat

The plot manipulations code above might seem custom. In reality, most

of the commands stay the same from one graph to another while the

functions' parameters change based on the data at hand. I will use the

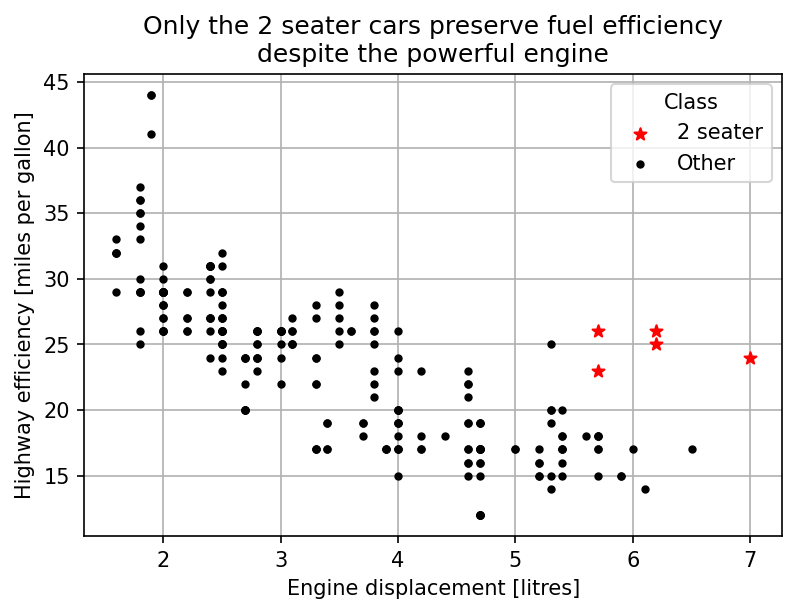

earlier mpg example to demonstrate this effect. The

resulting plot looks as follows:

Despite a different

plot type the fine tuning code was almost the same. The code for

vertical lines and tick modifiers did not offer additional clarity and

was removed along with the bar plot specific part. The only addition was

the title parameter for the legend. The resulting code is

shown below.

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

df_mpg = pd.read_csv("https://vincentarelbundock.github.io/Rdatasets/csv/ggplot2/mpg.csv", index_col=0)

df_2seaters = df_mpg[df_mpg['class'] == '2seater']

df_other = df_mpg[df_mpg['class'] != '2seater']

# plot preparation

plt.figure(figsize = (6,4)) # set the figure size (Width, Height)

ax = plt.gca()

# plotting

handle_2seater = plt.scatter(df_2seaters['displ'], df_2seaters['hwy'], color='red', marker='*')

handle_other = plt.scatter(df_other['displ'], df_other['hwy'], color='black', marker='.')

# fine tuning

plt.title('Only the 2 seater cars preserve fuel efficiency\n'

'despite the powerful engine')

plt.xlabel('Engine displacement [litres]')

plt.ylabel('Highway efficiency [miles per gallon]')

plt.grid(True)

ax.set_axisbelow(True)

plt.legend([handle_2seater, handle_other], ['2 seater', 'Other'], title='Class')

plt.savefig('pics/2seater.png', bbox_inches='tight', dpi=150)

plt.show()

Making plots faster to set up

The examples above demonstrated that some standard commands are

frequently used. Memorizing that code is not the biggest problem. The

main problem is that it takes a long time to put together the same lines

with slight changes for each plot. I will propose several strategies for

reducing the amount of effort required to memorize and put together the

code.

Change the defaults

Default plot settings can be changed in one place and propagated to

all the downstream figures in a jupyter notebook. For example, the

default grid behavior and the default figure size can be changed in the

following way:

plt.rcParams['figure.figsize'] = [5, 3]

plt.rcParams['axes.axisbelow'] = True

plt.rcParams['axes.grid'] = True

The full list of the settings, options, and the defaults can be found

here.

Rewriting the global defaults saves the coding time for the commands

that stay the same despite the context. However, the approach still

requires looking up the rcParams settings, adding these

settings to each new notebook, and typing content specific commands. The

next approach will take care of the content specific commands.

Copy and paste

This approach will take care of content specific commands. Just save

the template somewhere and copy it every time to finish the plot.

Content specific parts are easy to modify without memorizing all the

necessary commands. The template below works well for the majority of my

cases:

# plot preparation

plt.figure(figsize = (5,3)) # set the figure size (Width, Height)

ax = plt.gca()

# plotting

# fine tuning

plt.title('Title')

plt.xlabel('x')

plt.ylabel('y')

plt.grid(True)

ax.set_axisbelow(True)

ax.xaxis.set_major_formatter(plt.FuncFormatter(lambda value, tick_number: f"{value}" ))

handle_vline = plt.axvline(50, color='r')

plt.legend([handle_vline], ['reference'], loc='best')

plt.savefig('pics/file_name.png', bbox_inches='tight', dpi=150)

plt.show()

The template can be modified you use other commands quite a lot. The

major inconvenience with this approach is that you have to carry the

template around in a separate file and pull the code from that file

every time it is needed. Not the end of the world, but annoying.

Share the template across jupyter notebooks with magics

The %macro magic captures a piece of code for future

retrieval or execution. Just name the pattern and point the magic to the

jyputer cell that holds the template code. Say, the template code is in

cell 10 and I picked the name fine_tune for

it. The following command will associate the code with the name:

%macro -q -r fine_tune 10

By using the following command, the code can be retrieved

anywhere:

%load fine_tune

The next step is to make the template available for other notebooks.

The %store magic does the job. Its primary use is to share

the variables between the notebooks. fine_tune is one of

such variables. The following line stores template macro variable

internally:

%store fine_tune

The following command makes the template available in the notebook

where it is needed:

%store -r fine_tune

After that use %load fine_tune when you want to put the

plot together.

# # plot preparation

# plt.figure(figsize = (5,3)) # set the figure size (Width, Height)

# ax = plt.gca()

# # plotting

# # fine tuning

# plt.title('Title')

# plt.xlabel('x')

# plt.ylabel('y')

# plt.grid()

# ax.set_axisbelow(True)

# ax.xaxis.set_major_formatter(plt.FuncFormatter(lambda value, tick_number: f"{value}" ))

# handle_vline = plt.axvline(50, color='r')

# plt.legend([handle_vline], ['reference'], loc='best')

# plt.savefig('pics/file_name.png', bbox_inches='tight', dpi=150)

# plt.show()

%macro -q -r fine_tune 10

%store fine_tune

# retrieve in the new notebook if planning to use

%store -r fine_tune

import os.path

new_template_names = ['fine_tune']

# config folder path

ipython = !ipython locate

file_name = f'{ipython[0]}/profile_default/ipython_config.py'

# search patterns for commented and uncommented lines

exec_line_default = '# c.InteractiveShellApp.exec_lines = []\n'

exec_line = 'c.InteractiveShellApp.exec_lines = [\n'

# create the config files if not there

if not os.path.isfile(file_name):

!ipython profile create

# read the config file

with open(file_name) as f:

lines = f.readlines()

# uncommenting the part with line execution if commented

if exec_line_default in lines:

# find the commented line

setting_position = lines.index(exec_line_default)

# replace with uncommented

lines[setting_position] = exec_line

# add the closing bracket

lines.insert(setting_position+1, ']\n')

insert_position = lines.index(exec_line) if exec_line in lines else -1

# add the template loading lines

for template_name in new_template_names:

# shape the storage request line

new_line = f" '%store -r {template_name}',\n"

# add the line if not already there

if not new_line in lines:

insert_position += 1

lines.insert(insert_position, new_line)

# write the updated config file

with open(file_name, mode='w') as f:

f.writelines(lines)

Conclusion

Putting together a visualization that speaks for itself at a

stakeholder meeting is laborious. The number and variety of context

dependent commands that go with such graph makes the process hard to

automate and embed in a single plotting function. Memorizing the

commands is tedious. Typing these commands over and over for each new

visualization is time consuming.

In this post I showed how to use code templates to save time and

effort while finalizing the plot. Such template contains a set of most

used commands with placeholders for the context dependent parts. I also

showed how to load the template code fast using a jupyter magic.